When the Military Comes to American Soil

Domestic deployments have been generally been quite restrained. Can they still be?

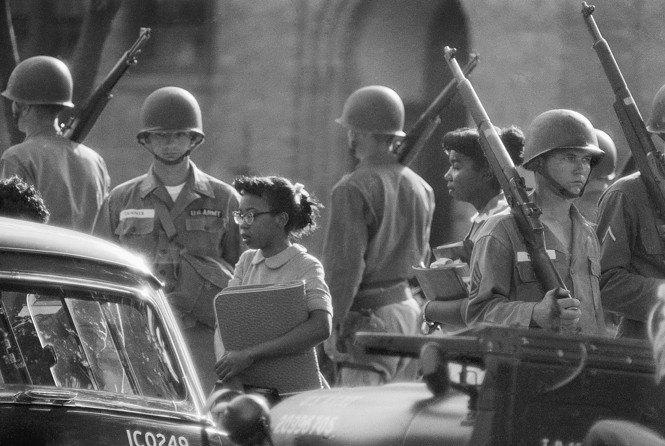

Domestic deployment of active-duty U.S. military, as is now taking place in Los Angeles, is both rare and perilous. Not since the 1992 riots in that same city has the country seen such a use of the armed services.. But that was a one-off. The more relevant, and worrying, parallel may be the period from 1957 to the end of 1968, when military forces actively patrolled U.S. soil on eight separate occasions. Perhaps the recent deployment is just the beginning—not a one-off, but a wave.

Those eight deployments resulted in just one fatality—a testament to remarkable restraint by the military. But many of the norms that fostered such restraint—bipartisan consensus, respect for institutional expertise, and well-planned rules of engagement—are today weaker, or gone altogether. What’s more, whereas U.S. marines were previously accompanied by Army military police trained in crowd control and de-escalation, they are now deployed alone, an unsettling break with past practice.

The 12 years spanning 1957 to 1968 were a period of great societal tumult and revolution, especially over race and the Vietnam War. Of the eight deployments, two were to enforce desegregation court orders, most famously at Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. Four were to quell riots, three of which were part of the numerous outbreaks across the country that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. And the remaining two were in response to protests: one to protect a famous 1965 march of civil-rights activists in Selma, Alabama, to push for the Voting Rights Act, and the other to tamp down a forgotten and chaotic attempt by anti-Vietnam protesters to blockade the Pentagon in 1967.

[Adam Serwer: The tyrant test]

That 1967 deployment was perhaps the most extraordinary. In a surreal prelude to the confrontation, as the rock band the Fugs played, Abbie Hoffman and Allen Ginsberg chanted to levitate the building, turn it orange, and exorcise its demons—a ritual humorously sanctioned in the protest permit. (The General Services Administration did, however, stipulate that the Pentagon could be levitated no more than three feet, to protect the building’s foundations.) Although roughly 50,000 demonstrators marched to the Pentagon, about 2,500 took part in a direct assault on the building. They surged up the steps—some smashed windows and tried to force open the doors, while others hurled objects and splashed paint on the soldiers stationed inside. Military police from the 503rd MP Battalion formed the first line of defense inside the entrance, physically blocking and repelling protesters who briefly breached the glass doors and entered the foyer. As pressure mounted, commanders deployed paratroopers from the 1st Battalion, 325th Infantry, 82nd Airborne Division, who engaged demonstrators outside the entrance and helped stabilize the scene. By day’s end, 21 civilians were reported injured—seven treated at the scene and 14 hospitalized—but, remarkably, no fatalities had occurred.

Indeed, this absence of lethal force proved typical: The only fatality caused by active-duty soldiers during this 12-year period occurred during the 1967 Detroit riots. The low number of deaths is at least partly why, except for the 101st Airborne’s deployment to Little Rock, most Americans barely remember these earlier domestic military interventions. Even in moments of widespread turbulence, the active-duty military exercised restraint overall. By contrast, people remember the Kent State massacre of 1970 because it was a bloody failure by the National Guard, during which four students were killed. Indeed, during this period, many police and National Guard units responded to unrest with heavy-handed tactics that resulted in many civilian injuries and fatalities.

The Army’s conduct during these deployments was far from flawless. In addition to credible allegations of excessive force, the Army carried out extensive domestic surveillance, often tracking civilians and protest groups without legal authority or oversight. And although its own use of force was generally restrained, its involvement helped blur the line between military and police roles. That blurring contributed to a long-term shift in civilian law enforcement—one that encouraged the adoption of military-style equipment and tactics, and helped lay the groundwork for the sort of aggressive police force that is common today.

What accounted for the Army’s restraint? Although society was as divided as it is today, political elites were not yet polarized and still placed trust in apolitical expertise. Leadership and lawyers at the Justice Department and the Pentagon, and leadership in the armed services, worked closely with senior officers in the Army to develop standing operating procedures and situation-specific rules of engagement aimed at minimizing the use of force.

Notably, that restraint came from the Army specifically, especially the military police. Historically, Army military police and infantry have often been deployed together during civil disturbances, but with distinct roles. Military police typically formed the first line of engagement with crowds, given that their regular duties—law enforcement, making arrests, and maintaining order on military bases—most closely resembled domestic policing. Infantry units, by contrast, were positioned as backup. After these deployments, the armed forces updated their guidelines to reflect and summarize the practices they had been implementing. That document, Operation Garden Plot, stated that troops were to use “minimum necessary force,” be courteous, and “avoid appearing as an invading alien force.” Military personnel were prohibited from loading or firing their weapons without the direct authorization of an officer, except in cases of self-defense where lives were in immediate danger.

The Marines—who have a reputation for lethality—were deployed only twice during this period: once during the 1967 protest at the Pentagon, where they appear to have played a minor role, and again amid the violent unrest in Washington, D.C., following King’s assassination. President John F. Kennedy considered sending them to help desegregate the University of Mississippi in 1962 but ultimately declined. And the Marines were held in reserve on several occasions: after MLK won his battle against Bull Connor in the 1963 Birmingham, Alabama, campaign for desegregation of downtown stores, during which firebombings of a civil-rights headquarters and King’s brother’s hotel room had sparked riots, and during the 1963 March on Washington.

Since the end of World War II, the Marines have been deployed domestically only once—until now. That earlier instance came during the 1992 Los Angeles riots. The reasons for the rareness of Marine domestic deployments are debated, but one likely factor is that past administrations may have considered the Marines’ reputed lethality ill-suited to sensitive domestic operations. Although Marine training is broadly similar to that of the Army infantry, the Corps has long cultivated a more aggressive combat identity. One of its unofficial slogans, once seen on bumper stickers and still available as a magnet, bluntly puts it: “United States Marine Corps—when it absolutely, positively has to be destroyed overnight.”

[Juliette Kayyem: Trump’s gross misuse of the National Guard]

More mundanely, the explanation may come down to logistics. The Marine Corps is a relatively small force and has rarely been stationed near sites of domestic unrest. However, Camp Pendleton—home to the largest concentration of Marines in the continental United States—sits just a few hours from Los Angeles and is far closer than the nearest viable Army unit, 45 miles south of Seattle. There may have been practical reasons to deploy the Marines. Still, the deeper question is whether this administration seriously weighed those trade-offs—or simply found it convenient that a force with such a fearsome reputation, one viewed by past administrations as a liability in domestic missions, happened to be nearby.

Most important, though, is this: Since 1945, no branch of the armed forces has ever been deployed for a domestic mission without military police as the initial line of contact. In that regard, what’s happening today in L.A. is truly extraordinary.

The political conditions surrounding the current deployment are dramatically different from those during that prior wave. Polarization has spread from society to the political elites, who now, more than ever, seek to use the military for political gain. On the Republican side, Donald Trump appears eager to deploy the Army against left-wing protesters. He has stacked the Justice Department and the Pentagon with personal loyalists, and has tended to bypass the Office of Legal Counsel—the institution traditionally responsible for vetting the legality of executive actions. Although the standard guidelines and procedures for past domestic deployments remain on the books, there is substantial reason to doubt that the civilian leadership will follow them.

Yet some institutional checks continue to function, even if unevenly. The federal judiciary has been a source of significant pushback against the administration. Already, a federal district court judge in California has ruled that Trump’s deployment of the National Guard in California was illegal (though the ruling was almost immediately put on hold for further review). But the Marines remain deployed, the legal authorities and precedents granting the president power over domestic deployments are broad, and the Supreme Court tends to be highly deferential to the president in this area.

Within the armed services, trained and principled leaders remain in place and prepared to navigate these challenges with discipline and integrity. However, they face an uphill battle against increasing pressure from above and must continue to respect the principle of civilian control of the military. The recent dismissal of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the judge advocate generals has sent a chilling message to the military: Disagreement with the administration’s edicts may come at a steep cost.

In the past, military deployments have been forgotten because the wave of unrest broke gently. This time, however, the wave may crash violently, and the wreckage it leaves behind could be substantial: to the Army’s legitimacy, to the health of American democracy, and to the civilian lives it may cost.

*Illustration by Akshita Chandra / The Atlantic. Sources: Jim Vondruska / Getty; Bettmann / Getty.