Trump’s Mass-Deportation Campaign Hasn’t Really Started Yet

The Trump administration’s campaign to remove millions of people from the United States could soon be supercharged by Congress.

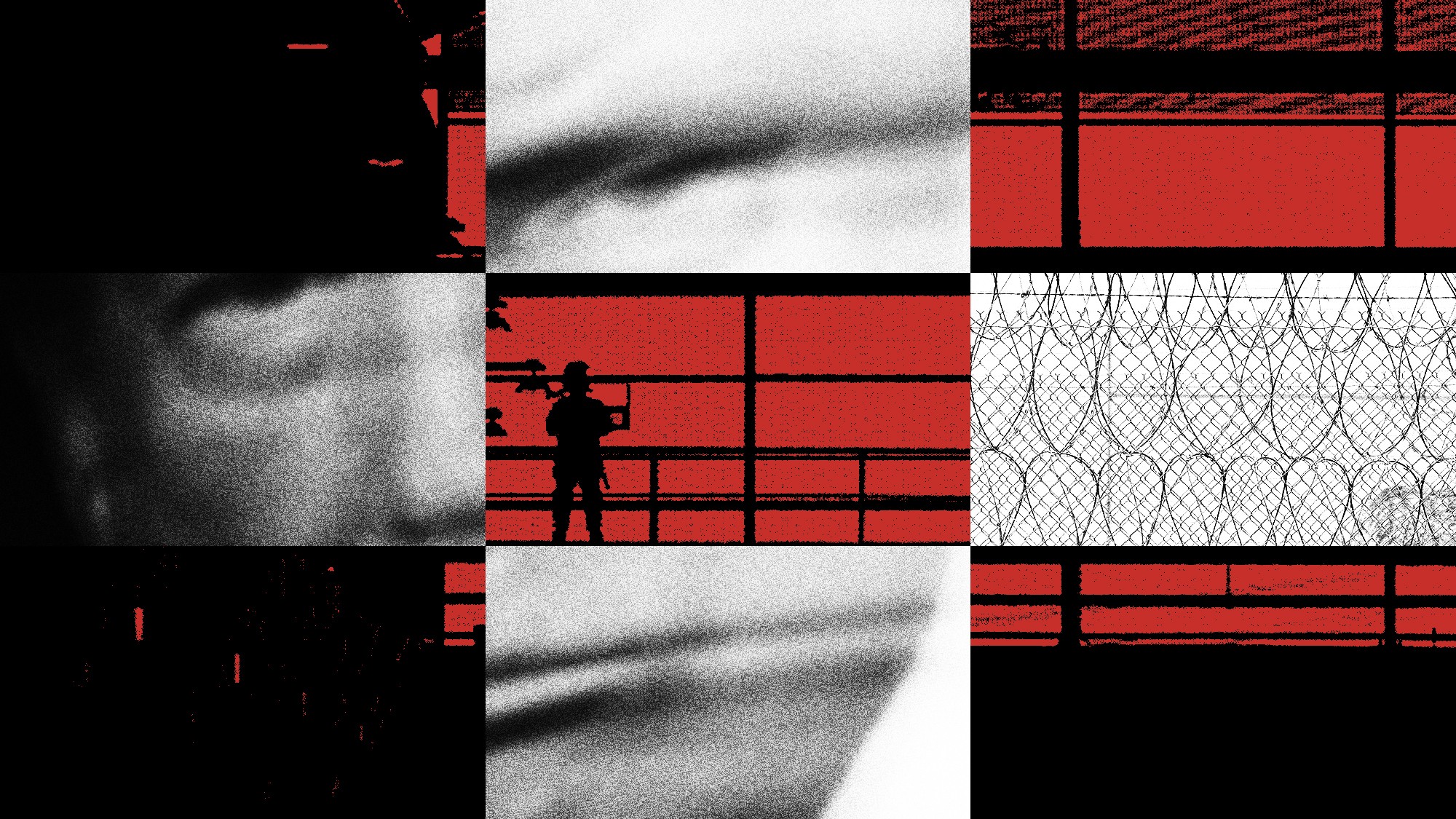

The Trump administration is working hard to convince the public that its mass-deportation campaign is fully under way. Over the past several weeks, federal agents have seized foreign students off the streets, raided worksites, and shipped detainees to a supermax prison in El Salvador using wartime powers adopted under the John Adams administration.

The tactics have spread fear and created a showreel of social-media-ready highlights for the White House. But they have not brought U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement much closer to delivering the “millions” of deportations President Donald Trump has set as a goal.

“We need more money,” Tom Homan, Trump’s “border czar,” told me in an interview. “We won’t fail if we get the resources we need.”

Using the budget-reconciliation process, Republican lawmakers are now preparing to lavish ICE with a colossal funding increase—enough to pay for the kind of social and demographic transformation of the United States that immigration hard-liners have long fantasized about achieving.

[Read: They never thought Trump would have them deported]

Although GOP factions in the House and Senate have squabbled over the contours of the bill, spending heavily on immigration enforcement has bicameral support. The reconciliation bill in the Senate would provide $175 billion over the next decade. A House version proposes $90 billion.

To put those sums in perspective, the entire annual budget of ICE is about $9 billion.

The funding surge—which Republicans could approve without a single Democratic vote—would allow ICE to add thousands of officers and enlist police and sheriff’s deputies across the country to help arrest and jail more immigrants. It would funnel billions to private contractors to identify and locate targets, jail them in for-profit detention centers, and fast-track their deportations.

Paul Hunker, who was formerly ICE’s lead attorney in Dallas, likened Trump’s deportation campaign to a gathering wave. “It seems intense now, but wait until five months from now when the reconciliation bill has passed and ICE gets a huge infusion of cash,’’ he told me. “If that money goes out, the amount of people they can arrest and remove will be extraordinary.’’

ICE officials envision a private-sector contracting bonanza that would rely on old workhorses such as CoreCivic and Geo Group-–the for-profit firms best known for running immigration jails—while enlisting large data companies to make the deportation system run more like an e-commerce platform.

This was a theme of ICE’s message to industry leaders at a border-security expo in Arizona last week. Keynote speakers included Homan, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, and acting ICE Director Todd Lyons.

“We need to get better at treating this like a business,’’ said Lyons, who added that he wanted a deportation system that would work like Amazon Prime “but with human beings.’’ His comments, first reported by the Arizona Mirror, drew condemnations from immigrant-advocacy groups.

Homan, who works out of ICE headquarters in Washington and enjoys direct access to the president, has insisted that the agency would prioritize criminals and gang members during the initial phase of the deportation campaign. Although plenty of noncriminals have already been targeted, the ratio will likely shift further toward people who have been living in the United States without attracting notice from law enforcement. Homan has likened his approach to a camera lens, saying that, with more funding, ICE can expand its “aperture” to include a broader range of immigrants. Anyone living in the United States without legal status will be fair game.

Since the inauguration, ICE has been under intense White House pressure to boost its deportation numbers. The agency remains hampered by financial and logistical constraints, and the administration’s deportation math is as fuzzy as its tariff formulas. ICE has essentially been told to remove four times as many immigrants as it did last year—to reach 1 million annually—without, at least so far, a corresponding increase in staffing or resources.

ICE carried out about 18,500 deportations in March, according to unpublished ICE data I obtained. That is down from 23,100 in March 2024, when illegal border crossings were much higher, giving ICE more easy-to-deport migrants. At the current rate, deportations are on pace to decline—not increase—during Trump’s first year in office.

With ICE unable to pad its stats with easy border removals, and sanctuary jurisdictions limiting the agency’s access to jails in cities with large immigrant populations, the path to 1 million deportations is steep. Finding and arresting immigration violators in U.S. cities and communities is the slowest and most resource-intensive way for ICE to operate.

Chad Wolf, who was an acting DHS secretary during Trump’s first administration and now works at the Trump-aligned America First Policy Institute, said a major cash injection from Congress will supercharge ICE.

“Once the funding is there, it’ll be a question of execution,’’ he told me. “There are many other steps it will take, but resources will no longer be the issue.’’

The pool of potential deportees may be 10 million or more. Trump officials have been lining up the next phase of their campaign by smashing the safeguards that some federal agencies have traditionally used to wall off sensitive personal information from the eyes of ICE.

The Internal Revenue Service, bowing to White House pressure, agreed this month to share with the Department of Homeland Security confidential data including the names and addresses of as many as 7 million immigrants who have been paying taxes despite lacking legal residency status. The IRS has long offered taxpayer-ID numbers to workers who lack U.S. legal status but wish to create a paper trail of faithful tax-paying in the hope that it would benefit their immigration cases. (Such workers cumulatively pay about $60 billion a year, according to the nonpartisan Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.) The arrangement worked because the IRS kept the data confidential.

[Stephen I. Vladeck: What the courts can still do to constrain Trump]

The Trump administration has been trying to enlist other federal agencies that previously kept ICE at arm’s length. Elon Musk’s DOGE team is helping ICE search for immigration violators by collecting data at Health and Human Services and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, The Washington Post reported Monday.

Millions of other deportation candidates are easier to find. In recent weeks the Trump administration has been trying to revoke the legal status of nearly 1.5 million immigrants who arrived during the Biden administration with a form of provisional residency known as parole. Another million or so who are living and working legally with temporary protected status are at risk of having their status revoked if the Trump administration prevails against legal challenges.

The two groups add up to about 2.5 million people whose names, addresses and other personal data are already known to DHS and ICE. The department has also threatened to charge foreigners with criminal violations if they do not register with the government and provide fingerprints within 30 days of arrival.

Tracking down people who are eligible for deportation and moving them out is the logistical puzzle confronting Homan. He said he wants to enlist private companies to optimize ICE enforcement.

ICE officers have been spending too much time on “targeting,” Homan told me, which is the process of identifying deportation candidates and researching their daily routines so that officers don’t come up empty when they try to make an arrest. ICE teams can’t force their way into a residence without a judicial warrant, so they try to determine when the person they want to grab typically leaves for work, or drops off kids at school. Then they can try to catch them in the open.

This is one example of the kind of data research Homan would like to hand off to private contractors. Reached by phone a day after the Arizona security conference, he sounded like someone who’d been listening to pitches from management consultants and data firms.

“You got all these companies out there that say they can help with targeting,’’ Homan said, mentioning firms such as Palantir and Deloitte, neither of which responded to inquiries. “There are a lot of smart people who can help cops be more efficient at what they’re doing.’’

ICE last week made a $30 million upgrade to its contract with the Denver-based data giant Palantir “to deploy new Targeting and Enforcement Prioritization, Self-Deportation Tracking, and Immigration Lifecycle Process capabilities,” federal contracting records show. It follows a separate modification last month for the company “to support complete target analysis of known populations.’’

Laura Rivera, an attorney who tracks contracts between tech companies and the Department of Homeland Security for the Just Futures Law project, attended the border-security expo and told me the message from Trump officials was that they are seeking to hire contractors to do “every task that doesn’t necessitate a badge and a gun.”

That includes social-media monitoring, immigration case management and the use of cellphone data to locate targets for arrest. The companies offering those services ‘’are looking to be the right hand of Trump in carrying out mass deportations,’’ she said.

Homan says his task is to reverse-engineer the record influx that occurred during the first three years of the Biden administration, when illegal border crossings averaged 2 million per year, the highest levels ever recorded. To reach industrial scale, ICE needs to think more like a logistics company than a law-enforcement agency, Homan said, “kind of like DHS or FedEx.’’

‘’How do we get people from numerous locations across the country? What’s the most efficient way to get them to a flight?’’ he asked.

Brad Youngman, the sheriff of Daviess County, Kentucky, told me he was somewhat surprised this month to see his department show up on an ICE website listing jurisdictions that have agreed to help the Trump administration arrest and deport more immigrants. Daviess County, a farming area along the Ohio River, is one of nearly 450 jurisdictions on the list, which is dominated by counties and police departments in Florida, where Republican Governor Ron DeSantis has led a push to make the agreements mandatory.

Youngman said a friend at ICE had encouraged him to sign up for the partner program, known as 287(g) for its section in U.S. immigration law, but he hasn’t fully committed yet. Federal task forces are a trade-off, Youngman reasoned, and he’s not sure yet whether his county will benefit from having deputies doing immigration work if it detracts from routine law enforcement or seems overzealous.

“I’ve got a lot of problems here that I need to focus on, so I’d like to hear more information,” Youngman told me. “I'm not necessarily looking to ruin people’s lives who are up here looking for a better way of life.”

Expanding the 287(g) program is crucial to Trump’s mass-deportation plan. It would allow the administration to deputize officers across the country for the deportation effort, and funnel federal money to states and counties politically aligned with the White House’s goals. Jurisdictions could apply for federal grants that would pay for vehicles, technology, overtime hours and more.

[Read: Trump dares the Supreme Court to do something]

Trump won Daviess County by 32 percentage points in November, but Youngman’s ambivalence is not out of the ordinary in conservative districts whose economies are heavily dependent on immigrant labor, law-enforcement experts told me.

Kiernan Donahue, the sheriff of Canyon County, Idaho, and the current president of the National Sheriff’s Association, said he has balked at joining ICE’s task force, even though he supports Trump’s enforcement agenda. “I don’t have the manpower,” he told me. If his deputies made more immigration arrests, he would have nowhere to hold them. The county jail facility he manages is full: “I have no bed space.”

Homan and ICE officials have been laying the groundwork for the next phase of the deportation campaign as they wait for congressional Republicans to deliver the money to pay for it. The administration has solicited contract proposals for a $45 billion expansion of immigration-detention capacity over the next two years, a request first reported by The New York Times. Separate ICE documents released through a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union show that the agency wants to add detention space in 10 states across the Midwest and West Coast.

ICE has the funding to pay for about 40,000 detainees a day, and is currently holding nearly 49,000, the latest agency data show. Homan has said he wants to boost detention capacity to more than 100,000.

In one sign of ICE’s ambitions, the agency has been looking to repurpose tent facilities along the Mexico border that were used extensively during the Biden administration as emergency processing sites for migrants. The facilities were the first stop for many of the millions allowed to pursue U.S. humanitarian protection during Joe Biden’s presidency. ICE will now run the process in reverse, and convert the tents into makeshift jails for detainees awaiting deportation.